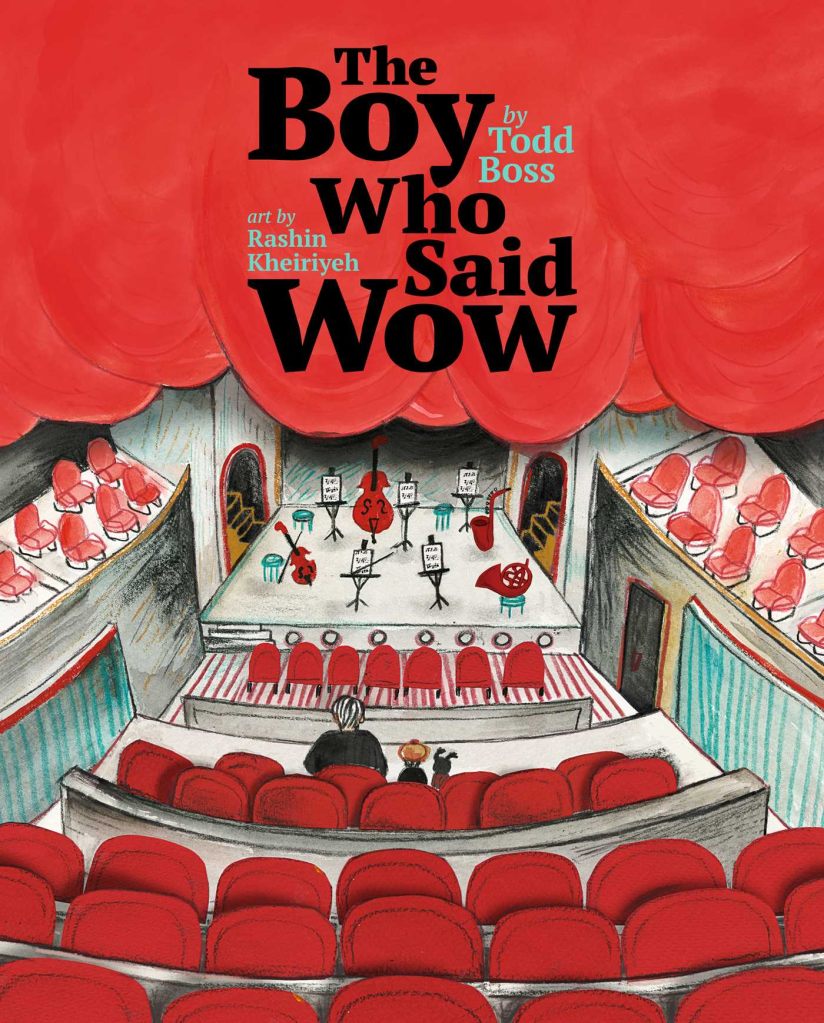

The Boy Who Said Wow by Todd Boss, illustrated by Rashin Kheiriyeh (Beach Lane Books, 40 pages, ages 4-8). Ronan is a boy who rarely speaks, and when Grandfather proposes a trip to the symphony, his parents are a bit skeptical. But Grandfather persists, and the two of them drive to the concert hall and find their seats. The lights go down, the music begins, and Ronan is swept away. In the moment of silence when the music ends, Ronan opens his mouth, and utters a loud, “Wow!” The audience laughs and claps, both for the orchestra and for Ronan. An author’s note shares that the story is based on an actual event that happened at Boston’s Symphony Hall in 2019. The illustrations look more like the 1950’s than 2019, but it’s a fun and interesting story with a sympathetic nonverbal main character.

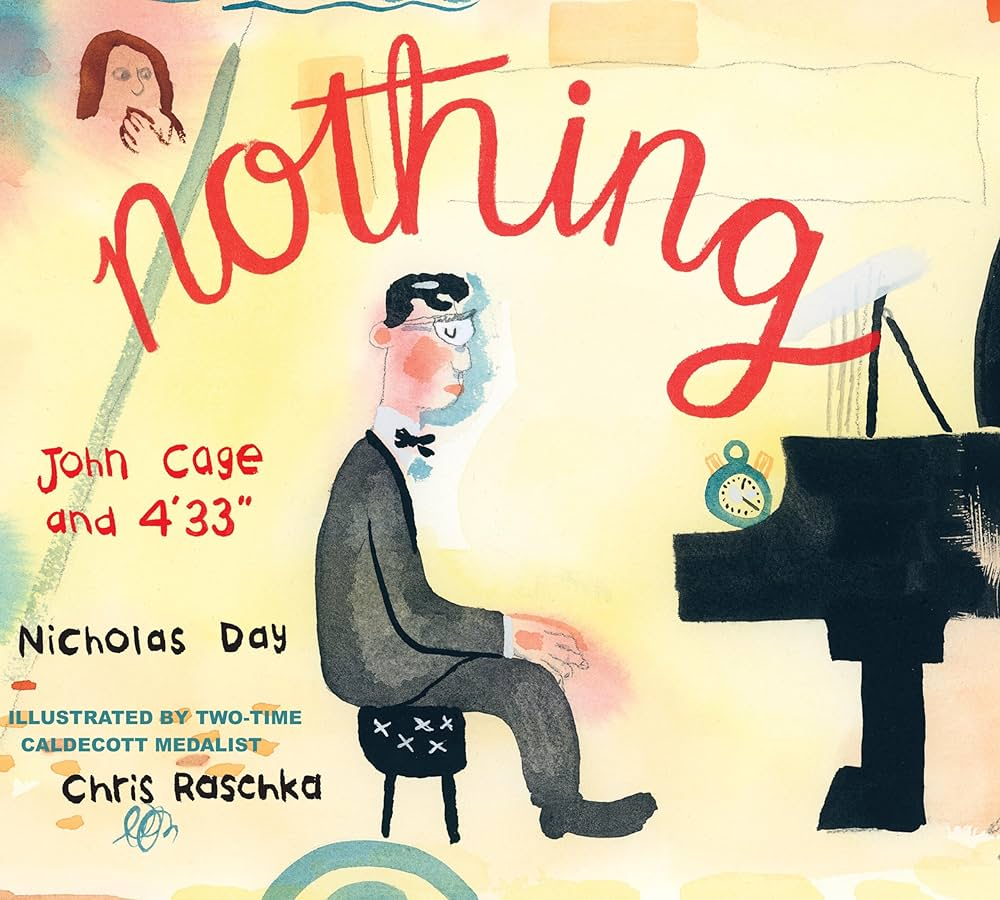

Nothing: John Cage and 4′ 33″ by Nicholas Day, illustrated by Chris Raschka (Neal Porter Books, 40 pages, grades 1-5). The story opens with a 1952 performance at the Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock, NY, where a pianist named David Tudor sits down at a piano and proceeds to do nothing for just over four and a half minutes. The word “nothing” is repeated a few times as the audience sits and wonders what is happening. The narrative then goes back 40 years to the birth of John Cage, a boy with unusually large ears and a penchant for inventing. Of all his radical compositions, his 4′ 33″ may be both the most unusual and the best-known. He wanted people to listen in the absence of sound to create their own music from what they heard around them. There’s an extensive author’s note, along with photos and a bibliography at the end.

The idea of this silent piece is fascinating and thought-provoking, stretching the boundaries of what can be considered music, and the subject is brought to life by Chris Raschka’s illustrations. The back matter seems more geared for older readers, and the concepts introduced may be a bit over the heads of the intended audience. Also, John Cage’s ears are described in a way that makes them sound freakishly large, but when I saw photos of him that seemed like an unnecessary exaggeration.

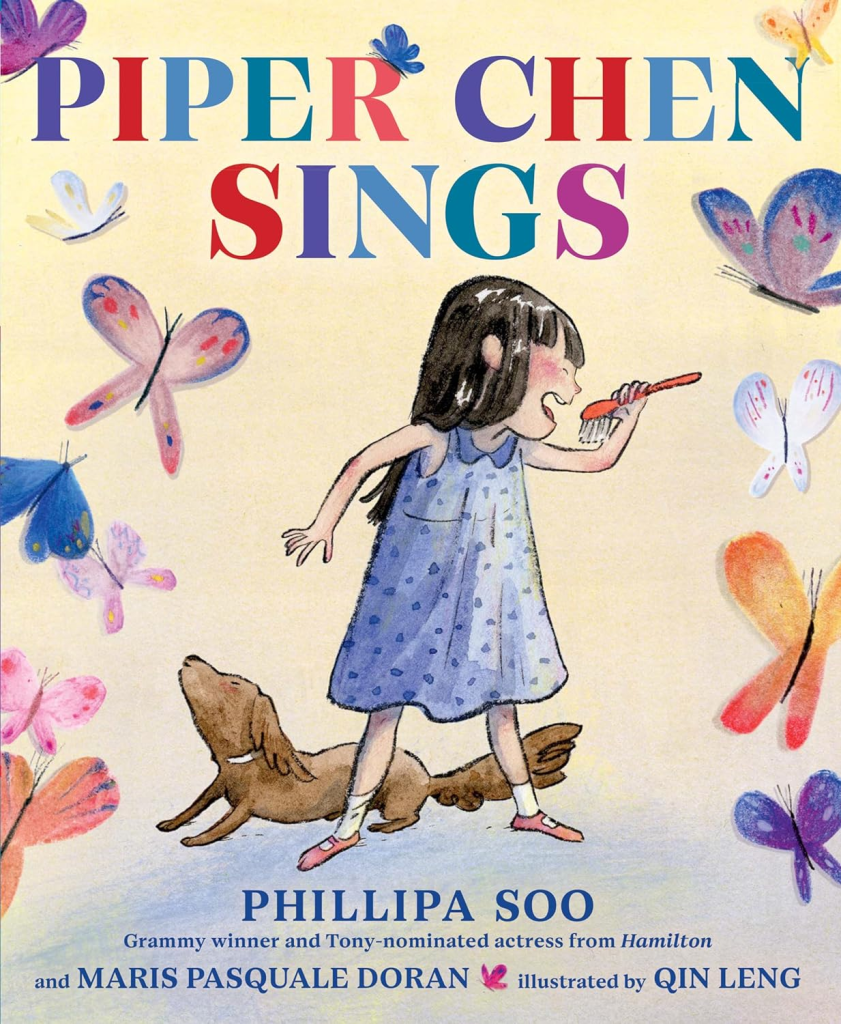

Piper Chen Sings by Philippa Soo and Maris Pasquale Doran, illustrated by Qin Leng (Random House Studio, 40 pages, ages 4-8). Piper loves to sing whenever she can, whether it’s joining the birds outside her bedroom window or performing for her stuffed animals. At school, she loves chorus, and when the teacher asks her to sing a solo in the spring concert, Piper offers an unequivocal “Yes!” But when it comes time to practice the solo, Piper gets stage fright and can’t do it. At home, she’s sad, no longer singing, until her grandmother Nai Nai has a talk with her, explaining that scary experiences can produce butterflies in the stomach, but so can exciting ones. Nai Nai is a pianist, and she tells Piper that the butterflies before a recital always settled once she started to play. Piper decides she will do the solo, and on the night of the concert, she welcomes the butterflies and feels them settle as she starts to sing. A lovely story by the Grammy-winning Hamilton actress that will show kids the importance of recognizing that fear and excitement often feel the same.