This summer I decided to travel to the Deep South. I flew to Nashville, rented a car, and drove to Alabama, Mississippi, and back to Tennessee, where I visited Memphis before returning to Nashville. Aside from a marching band trip to the Mardi Gras when I was 15, I’ve never traveled in this part of the country, and I was curious to experience it for many reasons.

Thanks in large part to books that I’ve read and reviewed here over the years, I have learned far more about Black history than I ever did in school, and I wanted to see some of the places that I’ve learned about. The history of the South continues to have an enormous impact on the United States today, and I wanted to experience for myself what this part of the country is like and to witness the ways that its history is told. I’ll be writing three posts to cover the eight days I spent on this trip.

I arrived in Nashville on July 3, with a plan to start in Birmingham on July 4. Yes, July 4. Not the best planning on my part, as both the 16th Street Baptist Church and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute were closed for the holiday. I made a quick stop so that I could at least see the outside of the church, then drove on to Montgomery.

I started my tour of Montgomery the next day with a trip to the Rosa Parks Museum and Library. The museum does a great job of bringing Rosa Parks’s contributions to life with a re-enactment of her bus ride and arrest, and plenty of artifacts and information about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

One recurring theme for me on this trip was the marginalization of women in the civil rights movement, and it started at this museum. I learned that Rosa Parks and her husband lost their jobs and received death threats due to her activism, leading them to move to Detroit. There, Parks continued to work for civil rights, often embracing a more militant philosophy than Martin Luther King, Jr. She was included to the 1963 March on Washington, but only introduced and recognized, not invited to speak.

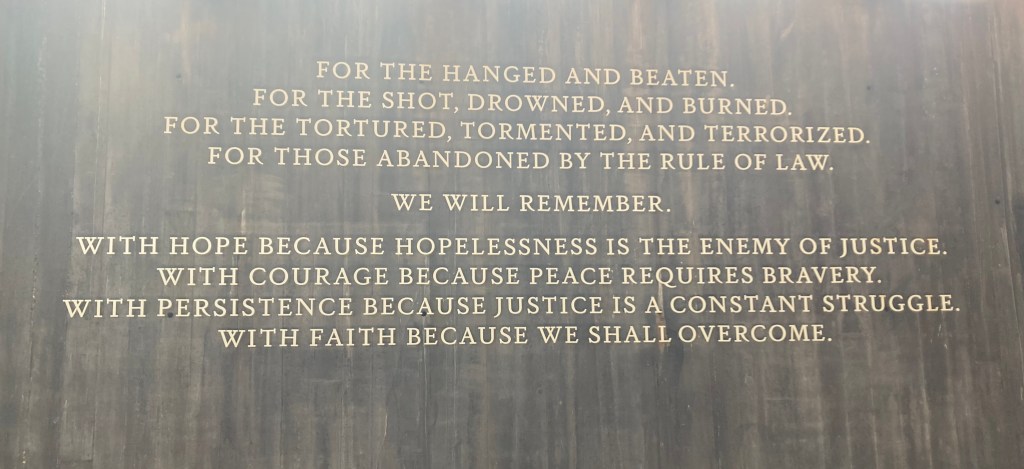

From there, I headed for the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum. These are both part of the Equal Justice Initiative, have a total admission fee of $5.00, and are about a five-minute drive from each other. I started at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial for the victims of lynching. It’s a 600-acre open-air space on top of a hill: a roof with slab after slab suspended from it, arranged by state and county, each one listing the victims of lynching in that county with each person’s name if its known, race, gender, and reason for and date of their murder.

The Legacy Museum’s full name is The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, and it explores the legacy of racism in America, beginning with the African slave trade and continuing through slavery, Jim Crow, chain gangs, and the mass incarceration of the Black population that continues today. There are lots of interactive exhibits, and it would be easy to spend most of the day at these two institutions.

They are hard places to visit, and probably best for middle school kids and older, but I wish every American could see them. I would suggest starting with the Legacy Museum. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is described as a “sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy,” and serves as a place to reflect on what is shown in the museum. I saw a man weeping in the middle of the Legacy Museum; you may want to plan on some breaks along the way.

I finished up in Montgomery at the Freedom Rides Museum, which provides an engaging history of the 1961 Freedom Rides, but after my other museum visits, I couldn’t help feeling discouraged by what I learned there. The Supreme Court ruled in 1946 that segregation on interstate buses was unconstitutional, but southern states ignored the ruling. The Freedom Riders endured a bus fire, arrests, and lengthy imprisonments in inhumane conditions just to finally get this 15-year-old ruling enforced.

I asked the tour guide about Diane Nash, whom I recently learned about from the book Love Is Loud by Sandra Neil Wallace. A leader in desegregating Nashville’s lunch counters and organizing the Freedom Rides, Diane is another woman who was key to the success of the civil rights movement, but whose name is not as well-known as many of the men. She continues her activism to this day, and I learned that, while Representative John Lewis agreed to record some of the narration heard in the museum, Diane Nash refused. The museum is run by the state of Alabama, and she didn’t want to support the state government in any way.

I had an AirBnB reserved in Newbern, Alabama, and drove through Selma on my way there. I saw a bridge ahead and realized it was the Edmund Pettus Bridge made famous by the brutal beatings of demonstrators on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, and by the Selma-to-Montgomery march. I stopped for a photo and walked around the interpretive center there. I had plans to visit the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute but felt too fried by my day to do much more.

A Black man approached me as I was heading for my car and told me that he had two uncles who were in the 1965 march. They were never bitter, he said, and believed that we are all “99.5% the same.” He and his wife are teachers, and he was selling a newspaper about their work mentoring local kids. He shook his head at the amount of gun violence in his community and the lack of political will to do anything to stop it. I found myself tearing up from all that I had seen that day, and after I bought a paper from him, we hugged at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Books about Alabama

Birmingham

Let the Children March by Monica Clark-Robinson (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018)

The Watsons Go to Birmingham–1963 by Christopher Paul Curtis (Delacorte Press, 1995)

The Youngest Marcher: The Story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, A Young Civil Rights Activist by Cynthia Levinson (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2017)

We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March by Cynthia Levinson (Peachtree, 2012)

Montgomery

Because Claudette by Tracey Baptiste (Dial Books, 2022)

Twelve Days in May: Freedom Ride 1961 by Larry Dane Brimner (Calkins Creek, 2017)

Rosa by Nikki Giovanni (Henry Holt and Co., 2005)

Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice by Phillip Hoose (Square Fish, 2009)

Rosa’s Bus by Jo S. Kittinger (Calkins Creek, 2017)

Rosa Parks: My Story by Rosa Parks (Puffin, 1999)

Sweet Justice: Georgia Gilmore and the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Mara Rockliff (Random House Studio, 2022)

Love Is Loud: How Diane Nash Led the Civil Rights Movement by Sandra Neil Wallace (Paula Wiseman Books, 2023)

Selma

Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom: My Story of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March by Lynda Blackmon Lowery (Dial Books, 2015)

Because of You, John Lewis: The True Story of a Remarkable Friendship by Andrea Davis Pinkney (Scholastic, 2022)

The Teachers March! How Selma’s Teachers Changed History by Sandra Neil Wallace (Calkins Creek, 2020)

Child of the Civil Rights Movement by Paula Young Shelton (Schwartz and Wade, 2009)

Janet, thanks for this post and book list…I’ve been wanting to make this trip for some time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Janet — I read your blog at least 2 to three times a week. What a wonderful trip and experience you had. Thank you so much for sharing. Looking forward to more reviews.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So sorry you missed the Civil Rights Institute here in Birmingham. It tugs at you and pushes you the same way the Legacy Museum does. So glad these places are keeping the conversations going and I’m glad people like you are seeking them out and sharing what they find. What a whirlwind tour!

LikeLike