This Is Orange: A Field Trip Through Color by Rachel Poliquin, illustrated by Julie Morstad (Candlewick, 48 pages, grades K-4). Which do you think came first, the color orange or the fruit? If you guessed the color, as I did, you’re in for a surprise to kick off this book that traces the history of the color, then meanders through the worlds of art, science, nature, and history looking for examples of it. Birds’ feet are orange, and so are cantaloupe and mimolette cheese. A color called International Orange that shows up in murky skies or seas is used for astronauts’ suits and the Golden Gate Bridge. You’ll find orange in Halloween jack-o-lanterns, Buddhist monks’ robes (from orange turmeric), and a number of countries’ flags. “Now it is time for you to find orange in your world,” the book concludes. “If you look carefully, you will see orange almost everywhere.”

Although the tone is lighter, this book reminded me of Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sky by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond, in that both books wake readers up to colors so common that we take them for granted. This would be a great book for an art class, or just to sharpen observational skills. I was disappointed there was no back matter, but the last page does a great job of sending readers off into the world with a new appreciation for the color orange.

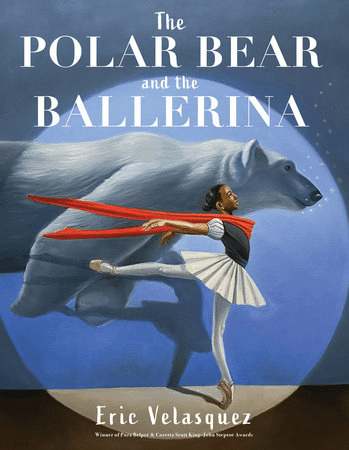

The Polar Bear and the Ballerina by Eric Velasquez (Holiday House, 48 pages, ages 4-8). A young ballerina and a polar bear bond at an aquarium in this wordless book. After the girl leaves with her mom, the bear notices that she’s left her long red scarf behind. Hoisting himself out of his tank, he walks across Manhattan to Lincoln Center, where he’s met with a “No polar bears allowed!” sign at the ticket window. His growl alerts the girl, who leaves the practice room to escort him inside to a seat. Despite disgruntled looks from his neighbors, the bear is enraptured by the show. Afterwards, he returns the scarf, then dances home, where he dreams about performing on stage with the girl. Endpapers give profiles of both the bear and the girl, a soloist at Harlem Children’s Ballet.

Kids will love the adorable polar bear and spunky ballerina in the gorgeous illustrations, and adults can use their story to facilitate conversations about making the arts accessible to everyone. For a moment, I thought ballerina Chloe Maldonado was a real girl, but then I realized the ballets listed on her resume are both books by Eric Velazquez! Those endpapers add some fun and depth to the story, though.