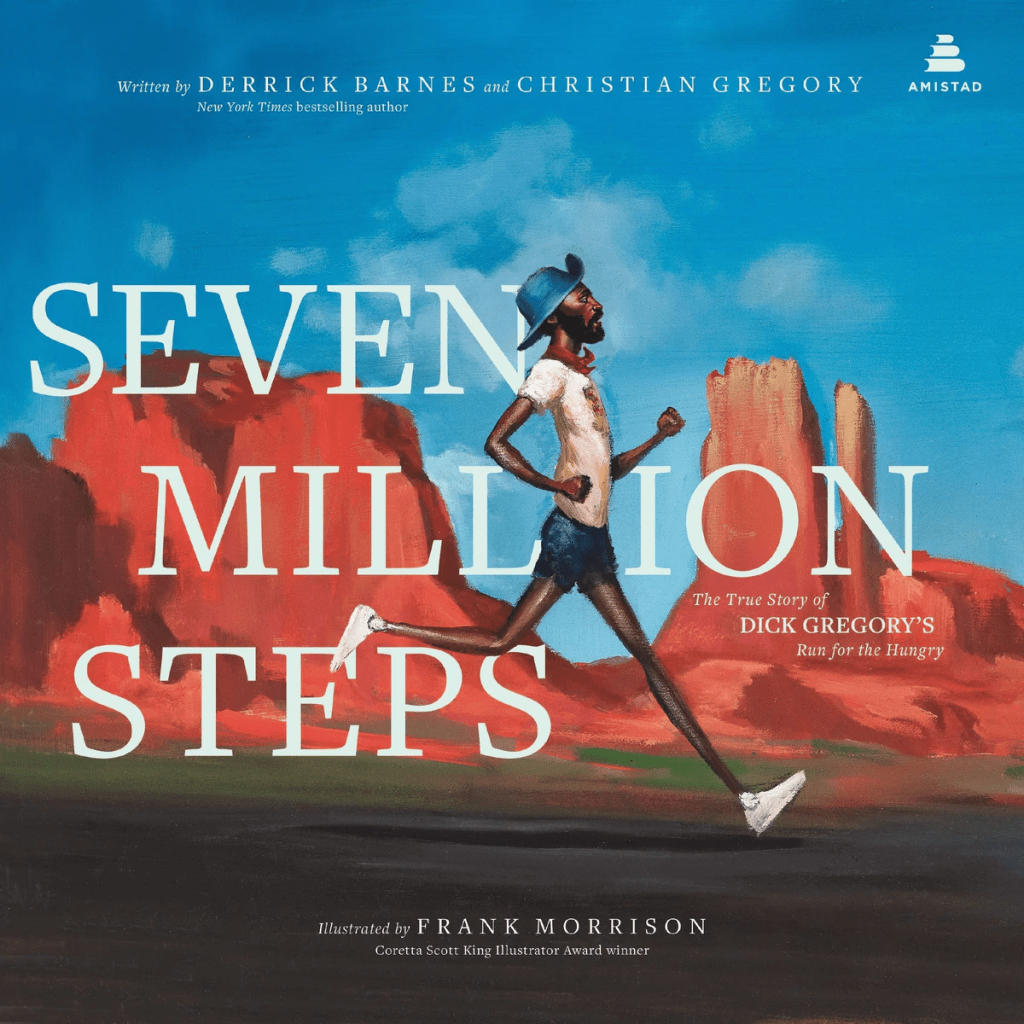

Seven Million Steps: The True Story of Dick Gregory’s Run for the Hungry by Derrick Barnes and Christian Gregory, illustrated by Frank Morrison (Amistad Books for Young Readers, 40 pages, grades 1-5). “What would you do if you knew someone who goes to bed every night without having supper?” This opening question is answered by an account of Dick Gregory’s 1976 run from Los Angeles to New York City: you would travel thousands of miles with very little food, subsisting mostly on juice, vitamins, and water to bring attention to those who are hungry across the country. You would cover 50 miles a day across twelve states, talking to anyone who would listen about what you’re doing and why. You would overcome pain and hunger to cross the George Washington Bridge into NYC on the Fourth of July, the 200th anniversary of the United States. Includes additional information about Dick Gregory’s run and hunger vs. food insecurity, as well as notes from the authors (one of whom is Gregory’s son) and illustrator, and three photos from the run.

I finished this book with more questions than answers and ended up spending some time learning about Dick Gregory and this run. His story is inspiring and is told here in a way to get kids to think about actions they can take to make the world a better place. I loved Frank Morrison’s illustrations showing different vistas of America and capturing the highs and lows of the run. I did find the story a bit confusing, particularly the second-person narration, which draws the reader in, but doesn’t give a straightforward account of the events. If you’re reading this to kids, be prepared to answer some questions.

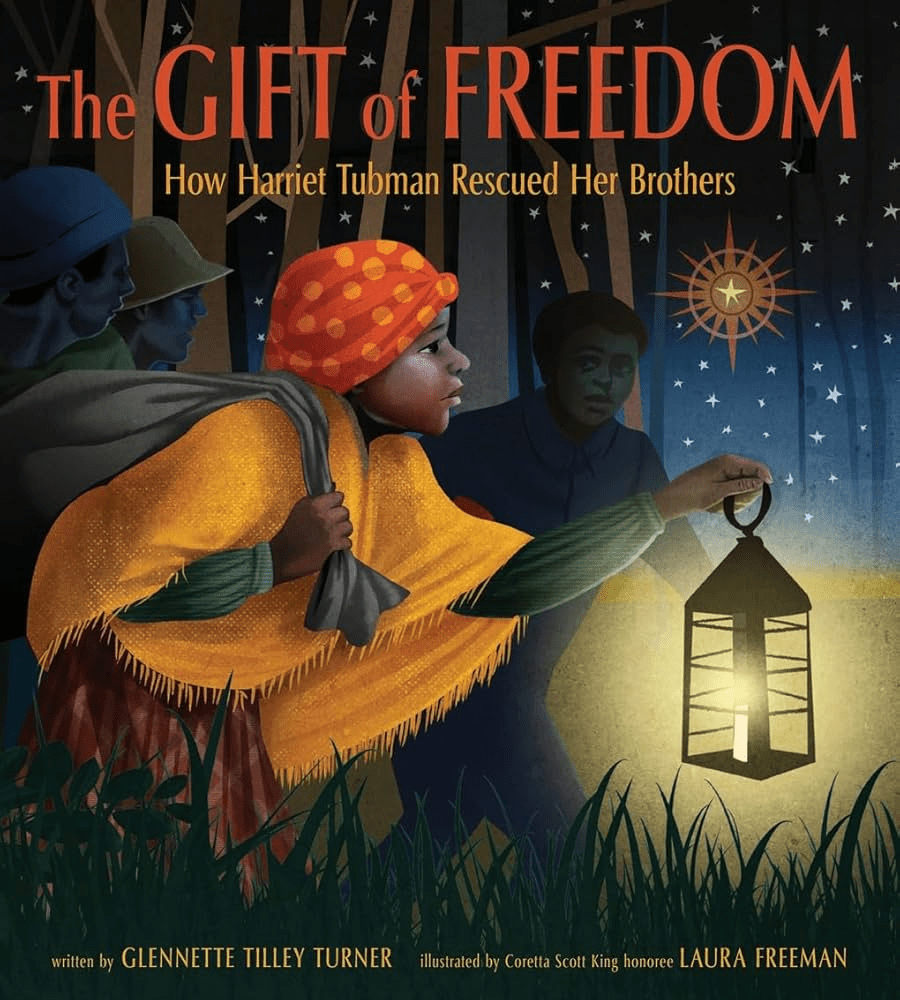

The Gift of Freedom: How Harriet Tubman Rescued Her Brothers by Glennette Tilley Turner, illustrated by Laura Freeman (Harry N. Abrams, 40 pages, grades 2-5). Starting with Harriet Tubman’s own escape in 1852, this book focuses on how Tubman helped others in her family find their way to freedom, specifically her three brothers. Her plan was to travel to Maryland at Christmas in 1854, when they were given permission to gather for a family Christmas dinner. The siblings met in secret at their parents’ home, where they were helped by their father, who averted his eyes or blindfolded himself so that he could honestly tell anyone who asked that he had not seen them. Following the familiar routes and safe houses that she had learned about, Harriet led her brothers to Philadelphia, where they were given new identities and put on a train to Canada. Includes a selected bibliography, a letter to readers, and an author’s note, which emphasizes how Harriet Tubman always learned as much as she could and befriended people with skills she lacked to allow her to be as successful as possible.

This compelling story with its striking illustrations offers plenty of drama and shows Harriet Tubman’s courage and skill that allowed her to help so many people escape slavery. The author’s note lists her other accomplishments helping to fight in the Civil War and working for women’s rights. The ending felt a bit abrupt, and there was no follow-up to the mention of Tubman’s attempts to rescue her husband, and I had to learn via other sources that he remarried and chose to stay in Maryland.